History

percussion caps – A Powerful Step Forward in Firearm History

In the world of early firearms, percussion caps made a major difference. When we speak of percussion caps, we refer to small metal caps containing a shock-sensitive explosive compound, placed on a nipple of a firearm and struck by a hammer to ignite the main charge. This ignition method offered huge improvements over the older flintlock system. In fact, the term “percussion caps” appears right at the beginning of this article because their role is central to the story of ignition technology.

From damp weather reliability to faster reloading, percussion caps dramatically changed how muskets, rifles, and pistols operated. Many historians mark the early 1800s as the period of transition when percussion caps began replacing flintlocks. For example, one account records that by 1830 percussion caps, attributed to Joshua Shaw (1815) had become the accepted ignition system for powder charges. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Over the next many paragraphs, we will explore how percussion caps work, why they mattered, their invention and spread, their use in warfare and hunting, the technology behind them, advantages and disadvantages, their legacy and how they paved the way for modern cartridge systems. Along the way I’ll draw on first-hand style insights, simple examples, and contrast features to keep the narrative engaging.

What are percussion caps & how do they work?

At its simplest, a percussion cap is a small metal cap—often made of copper or brass—containing a small charge of an impact-sensitive explosive compound (such as fulminate of mercury) which, when struck by the firearm’s hammer, ignites and sends flame through a “nipple” into the main powder charge inside the barrel. (Wikipedia)

Here’s how it works step‐by‐step:

- The shooter loads the main powder charge and bullet (or shot) into the barrel of a muzzleloader.

- A nipple is fitted at the rear of the barrel (where previously a touch hole or pan might have been).

- The percussion cap is placed firmly over the nipple.

- The firearm is cocked so the hammer is held back.

- When the trigger is pulled, the hammer falls, striking the cap.

- The explosive primer inside the cap detonates.

- The flame passes through the hollow nipple into the main charge.

- The main powder ignites, propelling the projectile down the barrel and out.

This mechanism offered notable improvements. For instance, it eliminated the need to pour priming powder into a pan (as in a flintlock) and exposed parts were reduced, so the system was far more weather-resistant. According to the Britannica entry: “By 1830, percussion caps … were becoming the accepted system for igniting firearm powder charges.” (Encyclopedia Britannica)

In more tangible terms: if you’ve ever flicked a toy cap pistol (the little popping sound), the principle is similar—an impact triggers a small explosion and sound. The real “percussion cap” is of course far more serious and precise.

You May Also Like: Fascisterne

The invention and early development of percussion caps

The story of percussion caps begins with dissatisfaction with flintlock systems. With flintlocks, a flint strikes steel to create sparks which ignite priming powder in a pan, then that ignites the main charge. But this system had many drawbacks: it was unreliable in damp weather, it required two types of powder (coarse for the main, fine for the pan), and the exposed pan could misfire. (nrablog.com)

In 1807, the Scottish clergyman Alexander John Forsyth patented a design using fulminating compounds (i.e., impact-sensitive chemicals) to ignite powder—this is the seed of the percussion cap concept. (museumoftechnology.org.uk)

In the following decade, various inventors and gun-makers refined the idea into a small metal cap. By the early 1820s, percussion caps were beginning to appear in firearms. One source says “the percussion cap was introduced in the early 1820’s”. (guns.fandom.com)

Then by about 1830, armies began adopting the system: “By 1830, percussion caps … were becoming the accepted system for igniting firearm powder charges.” (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Thus the timeline: early experiments in early 1800s → practical percussion caps in the 1820s → widespread adoption 1830s onward. One forum explained that percussion lock systems “began to replace flintlocks in large numbers by the 1830’s.” (The Muzzleloading Forum)

This gradual evolution shows how a single small innovation (the cap) had large downstream effects.

Why percussion caps were a game-changer

There are multiple reasons percussion caps represented a dramatic leap forward. Let’s list and explain them:

Improved reliability in bad weather. Because the priming compound in a cap was sealed and less exposed to the elements, firearms worked more reliably in rain or damp conditions—a big deal when flintlocks failed in wet weather. (texancultures.utsa.edu)

Faster and simpler ignition. The shooter no longer needed to handle separate priming powder in a pan; placing a cap on a nipple is quicker and simpler. This improved rate of fire and ease of use. (guns.fandom.com)

Safer, fewer misfires. The ignition mechanism was more contained; the hammer often had a hollowed face to reduce flying fragments from exploding caps, protecting the shooter’s eyes. (Wikipedia)

Ease of conversion from flintlocks. Many existing flintlock firearms could be converted to use percussion caps by replacing the pan and flint mechanism with a nipple and hammer—a relatively modest modification. (museumoftechnology.org.uk)

Foundation for modern ammunition. Although percussion caps themselves are not cartridges, the principle of a contained primer led directly to metallic cartridges and modern firearms. (Wikipedia)

In sum, percussion caps were a practical improvement that reduced complexity, increased reliability, and set the stage for future innovation.

The mechanism in detail: anatomy of a percussion cap

Delving a bit deeper into the device, the percussion cap consists of several parts and features worth noting:

- Cap shell or cup: Usually made of copper or brass, small cylindrical cup that fits over the nipple. (blog.bagunllano.com)

- Primer compound: Inside the cup is a small charge of impact-sensitive chemical—commonly fulminate of mercury, or a mix of potassium chlorate, fulminate, powdered glass, etc. (museumoftechnology.org.uk)

- Nipple (or cone): On the firearm, a hollow stem that extends from the chamber to the outside where the cap sits. When the cap is struck, flame passes through the hollow nipple to ignite the main charge. (Wikipedia)

- Hammer or striker: When fired, the hammer strikes the cap, crushing it and igniting the primer. Some designs hollow the face of the hammer to minimize cap fragments blowing back at the shooter. (Wikipedia)

As one blog summarised:

“Before percussion caps, firearms relied on flintlock systems, which were less reliable and slower to fire. The percussion cap simplified and improved ignition.” (blog.bagunllano.com)

Thus, the technology is compact but elegant: a small cap, a nipple, and the hammer. All together they enabled consistent ignition.

Historical adoption and military significance

The adoption of percussion caps had strong military implications. Once armies recognized the improved reliability, they began converting or issuing cap-lock rifles and muskets. For example:

- In the United States, the first percussion firearm produced for the military was a percussion carbine version of the M1819 Hall Rifle around 1833. (Wikipedia)

- In Britain, the famous Brown Bess musket was converted to caplock in 1842. (nrablog.com)

- The timeline shows by about 1825 percussion-cap guns were in general use in some places. (PBS)

The advantages we noted previously (weather resistance, reliability) mattered enormously in battle—especially in campaigns where rain, mud, and long exposure reduced the effectiveness of flintlocks. For instance, one account notes that during a British military exercise in 1842, troops armed with flint muskets could not fire because of rain, but those with percussion arms could. (korns.org)

In the American Civil War era, percussion-cap firearms dominated black-powder usage before the widespread adoption of metallic cartridges. The cap and ball revolvers and muzzleloaders of that period used percussion caps as the ignition method. (gunsandammo.com)

Thus percussion caps were central to mid-19th-century military small arms.

Impact on civilian use and hunting

Outside the military, percussion caps also changed hunting, sport shooting, and personal firearms. Hunters found that percussion cap firearms were far more reliable outdoors. The inconvenience and risk of flintlocks misfiring in damp woods or morning dew was greatly reduced by the cap system. Indeed, the invention of the cap was partly motivated by hunting needs: Forsyth’s original motivation was missing birds because of slow ignition and large smoke flash from his flintlock shotgun. (museumoftechnology.org.uk)

In addition, because conversions from flintlock were feasible, many civilian gunsmiths offered “altering flint locks to percussion” services in the 1830s. (korns.org)

Therefore, the percussion cap not only served war; it served everyday shooters, sportsmen, and frontiersmen. Its impact is felt in firearms collections, reenactments, and black-powder shooting circles to this day.

Advantages and limitations of percussion caps

Advantages

- Weather resistance: Less exposed priming area means better performance in damp conditions.

- Simpler operation: No separate priming pan; cap fits directly onto the nipple.

- Faster ignition: The sequence is shorter than flint-pan, improving rate of fire slightly.

- Easier conversion: Existing flintlock guns could be modified to caplock systems without complete redesign.

- Foundation for future tech: The small primer idea leads to enclosed cartridges and modern firing mechanisms.

Limitations

- Still muzzle‐loading: Many percussion cap firearms were still muzzle‐loaders, meaning slow reloading compared to later breech-loaders.

- Cap supply: Shooters required a supply of percussion caps; in remote locations supply could be limited.

- Manual placement: Each shot still required placing a cap; not as convenient as modern cartridges.

- Risk of chain firing: In revolvers or multi-chamber systems, ignition flashes could ignite adjacent chambers unless careful with grease or wads. (As noted in cap‐and‐ball revolver discussions) (gunsandammo.com)

- Eventually obsolete: With the advent of metallic cartridges and self‐contained primers, percussion caps became obsolete. The needle-gun and other innovations overtook the system. (Wikipedia)

In short, while percussion caps were a major step forward, they represented a transitional technology bridging flintlocks and modern firearms.

Key innovations and transitions enabled by percussion caps

The percussion cap did more than improve ignition; it enabled or accelerated several other technological transitions:

- Cap and ball revolvers: The ignition by percussion cap enabled the practical widespread use of revolvers like the Colt Paterson (1836) and others. (gunsandammo.com)

- Needle-gun and breech-loaders: The Dreyse Needle Gun (1841) used a paper cartridge and a “needle” to strike a percussion cap at the base of the bullet—the next step beyond simple caplocks. (Wikipedia)

- Metallic cartridges: The sealed primer concept eventually led to integrated primers inside brass cartridges. The mechanism of percussion cap ignition was the conceptual predecessor to modern primers. (Wikipedia)

- Conversion markets: Many flintlock arms were converted to percussion systems—signaling the practical and economic impact of the invention. (korns.org)

Thus percussion caps represent a hinge point in firearms technology: innovation from older systems and a precursor to modern ammunition.

Design variations, sizes and manufacturing

While the basic concept of percussion caps is simple, in practice there were many design variations to suit different firearms (muskets, rifles, pistols) and manufacturers. For example:

- Caps came in different sizes—appropriate to the size of the nipple and the firearm’s design. (guns.fandom.com)

- Some were made of copper, others brass, and early experiments used steel caps. (Wikipedia)

- Manufacturing grew into a large industry. For instance, a forum post notes that the U.S. company Crittenden & Tibbals, starting in 1849, made many millions of percussion caps, including 80 million in one year (1860) for military use. (forum.cartridgecollectors.org)

- Some caps were improved to reduce fragmentation when struck: e.g., improved designs to prevent shards flying back toward the shooter. (korns.org)

These details underscore the practical manufacturing and supply-chain dimensions of percussion cap technology—they weren’t just theoretical, they were mass-produced items with important manufacturing implications.

Conversion of flintlock arms to percussion systems

A large portion of the adoption of percussion caps came via conversion of existing flintlock firearms rather than only new builds. The reason: many armies and private owners already possessed large stocks of flintlock muskets, rifles or pistols. Converting them to the new cap‐lock system made economic sense.

Typical modifications included:

- Removing or replacing the flintlock pan and frizzen.

- Drilling and fitting a hollow nipple where the pan or touch-hole was.

- Modifying the hammer (or cock) so it could strike the cap properly (often with a hollowed face).

- Sometimes adjusting the breech or barrel opening for more reliable ignition.

From historical sources: one summary notes that about 80% of all flintlock rifles and shotguns were converted to the percussion principle from roughly 1835 to 1855. (korns.org)

Thus the adoption curve was not just new models; it was large-scale retrofit, which accelerated the spread of percussion caps across both civilian and military arms.

The broader historical context and timeline

Let’s sketch a compact timeline to place percussion caps in historical context:

- 1807: Forsyth patents ignition using fulminates (early percussion concept). (museumoftechnology.org.uk)

- Early 1820s: Practical metal percussion caps are introduced and begin to appear in firearms. (guns.fandom.com)

- 1830: Percussion caps become widely accepted in some regions. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- 1835-1855: Large-scale conversion of flintlock firearms to percussion systems. (korns.org)

- 1840s: Military adoption ramps up; for example British Brown Bess converted in 1842. (nrablog.com)

- Mid-19th century: Peak of percussion-cap firearm use (muskets, rifles, cap-and-ball revolvers) before metallic cartridges and breech-loading systems dominate. (The Muzzleloading Forum)

In short: percussion caps mark the intermediate era between flintlocks and modern cartridge firearms—a vital evolutionary step.

Real-world example: percussion caps in action

Imagine a frontier civilian in the 1840s hunting in damp woods. Under the flintlock system, moist priming powder in the pan might misfire; the flint may not strike properly; the smoke flash might alert game. With a percussion cap-armed rifle, the shooter simply places a cap, loads powder and ball, cocks, and fires with greater confidence—even if the morning dew is heavy.

Likewise, a soldier in a rain-soaked field can fire a percussion-cap musket where flintlocks might fail. Reports from the time indicate this improved reliability was noticed in combat scenarios. For instance, one note from 1842 recounts: “a detached company of our troops, armed with flint muskets, was surrounded … unable to fire a shot … our troops supplied with percussion arms” fared better. (korns.org)

Thus in both civilian and military contexts, percussion caps brought tangible benefits. The modest metal cap may seem insignificant, but it delivered meaningful improvement.

Collecting, reproduction and modern interest

Today, percussion-cap firearms and accessories are of interest to collectors, historians, reenactors, and black-powder shooting enthusiasts. Original percussion caps, cap-and-ball revolvers, converted muskets and rifles all have value.

Because original caps and firearms may be delicate or rare, many manufacturers produce replicas of percussion-cap weapons (especially revolvers) for historical shooting. For example, the article on cap-and-ball revolvers notes that nearly every popular model is available as a reproduction. (gunsandammo.com)

For the hobbyist wanting to shoot a percussion-cap firearm: one must use correct black-powder or substitute, ensure nipples and caps are compatible, use proper safety procedures (e.g., ensuring caps are seated fully, avoiding premature ignition, cleaning residue promptly). The design may feel slow compared to modern firearms, but it provides a unique historical experience.

The legacy: how percussion caps paved the way for modern ammunition

Although percussion caps themselves became obsolete with the rise of metallic cartridges, their conceptual significance cannot be understated. Key legacy points:

- The idea of a separate but self-contained primer (the cap) directly influenced the development of cartridges that combined primer, powder, and projectile in one unit. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- The improved reliability and weather resistance of cap ignition demonstrated the value of sealed ignition systems.

- The industrial manufacturing of percussion caps (millions produced) laid groundwork for mass-production of ammunition and primers. (forum.cartridgecollectors.org)

- The conversions of flintlock firearms to percussion systems showed that incremental innovation, not just radical new designs, can have widespread impact.

In effect, percussion caps form a bridge between the romantic age of muskets and the modern era of cartridges. They are a testament to how seemingly small components can shift entire technological landscapes.

Considerations for antique firearms enthusiasts

For anyone dealing with firearms that use percussion caps or are converted to cap-lock systems, some practical considerations:

- Ensure correct nipple and cap size: Use the appropriate size percussion cap for the firearm; wrong size can lead to mis-seating or blow-back.

- Inspect nipples for wear or deformation: Over time, nipples can degrade, affecting reliable ignition.

- Use quality percussion caps: Modern replicas are available, but one must ensure compatibility and safety.

- Clean residue: Black powder leaves heavy residue; after firing multiple shots, nipples and barrels must be cleaned to maintain reliability.

- Safety with chain-fire risk: Especially in revolvers, ensure that ignition of one chamber cannot accidentally ignite adjacent chambers. Use proper wads or grease as historically practiced. (gunsandammo.com)

- Legal / regulatory considerations: Depending on jurisdiction, antique firearms and black powder shooting may require special permissions or compliance.

By following these practices, the historical experience can be enjoyed safely and responsibly.

Conclusion

In the grand sweep of firearms history, percussion caps occupy a vital but often overlooked niche. They served as the ignition bridge between flintlocks and modern cartridges. Their introduction simplified operation, improved reliability, and allowed firearms to perform better in challenging conditions.

While the metal cap itself may look small and simple, its impact was large. It empowered soldiers, hunters and shooters to rely less on weather luck, to fire with greater confidence and to benefit from improved technology. The evolution from flint to percussion to metallic cartridges exemplifies how incremental innovation can drive major change.

Today, collectors, reenactors and historians honour percussion-cap firearms not just as curiosities, but as embodiments of a key technological shift. If you ever pick up a percussion-cap rifle or revolver, you’re engaging with a piece of engineering heritage—one that literally struck a spark, and changed the course of firearms design.

Music7 months ago

Music7 months ago[Album] 安室奈美恵 – Finally (2017.11.08/MP3+Flac/RAR)

Music7 months ago

Music7 months ago[Album] 小田和正 – 自己ベスト-2 (2007.11.28/MP3/RAR)

- Music7 months ago

[Single] tuki. – 晩餐歌 (2023.09.29/Flac/RAR)

- Music7 months ago

[Album] back number – ユーモア (2023.01.17/MP3/RAR)

Music7 months ago

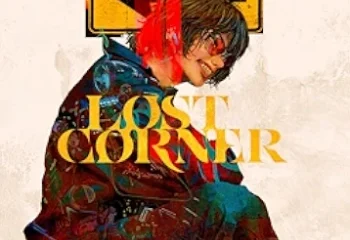

Music7 months ago[Album] 米津玄師 – Lost Corner (2024.08.21/MP3 + Flac/RAR)

- Music7 months ago

[Single] ヨルシカ – 晴る (2024.01.05/MP3 + Hi-Res FLAC/RAR)

Music7 months ago

Music7 months ago[Album] ぼっち・ざ・ろっく!: 結束バンド – 結束バンド (2022.12.25/MP3/RAR)

Music7 months ago

Music7 months ago[Album] Taylor Swift – The Best (MP3 + FLAC/RAR)